A key challenge commonly faced in distributed systems design has to do with process coordination. Many large scale systems require efficient ways to coordinate between servers, and there are variations on the purpose of coordination (e.g. node configuration, group membership etc.) each with different requirements. Thus, developing a service best suited for a particular application from scratch can be challenging and time consuming.

Introducing ZooKeeper, first described in a paper published by Yahoo!, a service used for coordinating processes in distributed systems. Authors of ZooKeeper call it a coordination kernel as it exposes an interface that allows clients to build coordination primitives (e.g. locks, condition variables) without changes to the underlying service, much like an operating system provides system calls for user-space processes. Contrast this with services that targets a specific use case, such as the Akamai Configuration Management System for node configuration, or the Amazon Simple Queue Service for queuing, ZooKeeper is much more flexible, which allows clients to build arbitrary primitives for specific use cases.

“Distributed systems are a zoo. They are chaotic and hard to manage, and ZooKeeper is meant to keep them under control.”

- on the origin of the name "ZooKeeper"

One of the advantages of ZooKeeper is the emphasis on being “wait-free”, meaning that its implementation does not make use of blocking primitives, such as locks. This avoids common problems where slow/faulty clients become the bottleneck in the system. Yet surprisingly, this does not prevent the implementation of locks as we will see later on. That being said, in order to be an effective service for coordination, ZooKeeper must provide some reasonable guarantees.

In this article, we will discuss the basic ZooKeeper API and its semantics, the guarantees that come with ZooKeeper, some example implementations of common primitives, as well as discuss the underlying implementation of ZooKeeper itself.

The ZooKeeper Service

The Abstraction

The ZooKeeper service is usually composed of an ensemble of ZooKeeper servers. Clients of the service (which are processes that you want to coordinate) connect to the service by obtaining a session handle from a particular server, but the handle itself persist across ZooKeeper servers, which allow clients to transparently move from one server to another.

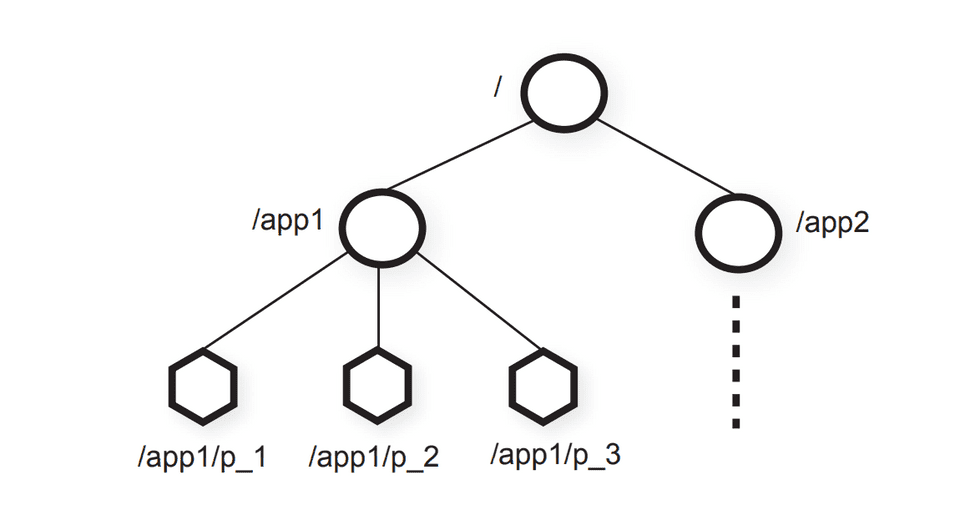

The abstraction that ZooKeeper provides is a set of data nodes, organized according to a hierarchical name space, which is a close analogue of files in a typical filesystem. Each data node is stored in-memory, and can contain arbitrary data, but is not designed for data storage, but more for coordination metadata.

In particular, there are two types of data nodes that can be created:

- Regular: Clients create and delete regular nodes explictly.

- Ephemeral: Clients create ephemeral nodes and can delete them explicitly, but the system can remove such nodes automatically when the session that created the node terminates.

Note that ephemeral nodes can be useful for implementing certain primitives that are dependent on whether specific nodes are connected (e.g. leader election, group membership).

Further, each data node can be created with the sequential flag. Nodes created with the flag will have a monotonically increasing counter assigned and appended to its name. This can be useful for implementing primitives that require queuing.

Finally, ZooKeeper also provides a watching facility, much like subscription services/change streams, which allows clients to receive a notification of a change without polling. This can be useful for implementing primitives that require event waiting or callbacks.

Client API

Clients of the ZooKeeper service issue requests through the client API. We present a basic subset of the API discussed in the paper, which we will use to build some primitives later on.

create(path, data, flags): Creates a data node with path namepath, storesdata[]and returns the name of the data node.flagsallow a client to select between regular and ephemeral data nodes, as well as make the data node sequential.delete(path, version): Deletes the data node atpathif the version number matches the data node.exists(path, watch): Returns whether a data node atpathexists. Thewatchflag enables the client to watch the data node for changes.getData(path, watch): Returns the data associated with the data node. Thewatchflag enables the client to watch the data node for changes.setData(path, data, version): Writesdata[]to the data node atpathif the version number matches the data node.getChildren(path, watch): Returns the set of children names of a data node.sync(path): Waits for all updates pending at the start of the operation to propagate to the server that the client is connected to.

Note that these requests can be issued asynchronously. In particular, multiple requests can be issued from the same client at a time.

ZooKeeper Guarantees

A coordination kernel would be next to useless without reasonable guarantees about how it behaves when operations interleave. Thus, ZooKeeper provides the following guarantees.

- Linearizable writes: All requests that update the global state of the ZooKeeper ensemble are serializable and respect precedence. This means that the outcome of a set of possibly interleaving writes is equal to the outcome of those writes executing serially. Further, write requests are always processed in order.

- FIFO client order: All requests from a given client are executed in the order that they were sent by the client.

Note that ZooKeeper was designed for read-heavy workloads (target read-to-write ratios range from 2:1 to 100:1), thus ZooKeeper does not support linearizable reads! In other words, reads from a given server can be stale, meaning that updates that are committed to global state might not be visible. This is a conscious design decision and does not affect the correctness of the primitives we can build with ZooKeeper if done carefully. We will discuss why this occurs when we discuss the implementation details of the ZooKeeper service later on.

Basic Coordination Primitives

Having seen the abstraction, client API and guarantees of ZooKeeper, let us put it in action and build a couple of simple coordination primitives with ZooKeeper, namely read-write locks and leader election.

Read/Write Locks

A read-write lock is a locking primitive allows multiple readers to hold the lock

or exactly one writer to hold the lock at one point in time. To build such

a primitive, we create a regular data node at path l to hold metadata for

a particular lock. Then, for each client wishing to hold the lock for reading or

writing, we line them up by creating a sequential data node, and watch the

data node ordered just in front of the newly created node for changes.

The following pseudocode describes the logic in more detail.

Write Lock

1 n = create(l + “/write-”, EPHEMERAL|SEQUENTIAL)

2 C = getChildren(l, false)

3 if n is lowest data node in C, exit

4 p = data node in C ordered just before n

5 if exists(p, true) wait for event

6 goto 2Read Lock

1 n = create(l + “/read-”, EPHEMERAL|SEQUENTIAL)

2 C = getChildren(l, false)

3 if no write data nodes lower than n in C, exit

4 p = write data node in C ordered just before n

5 if exists(p, true) wait for event

6 goto 3Unlock

1 delete(n)A couple of interesting points to note:

- The sequential flag came in useful to implement queuing for locks. Since reads can easily be stale, allowing the server to choose the concrete data node path prevents race conditions that typically happen due to the lack of atomicity of a read followed by a write.

- The ephemeral flag made sure that clients that disconnect due to a failure or without releasing the lock on exit will not hold the lock indefinitely.

- The familiar loop to check whether a lock has been obtained by the client is important, since it is possible that the previous lock request in queue was abandoned (say by a disconnection) while an earlier client is still holding the lock.

- The watch facility provided by ZooKeeper is a neat way to notify a client that they can attempt to obtain the lock without polling.

- There is no herd effect since exactly one client is woken up when a lock is released.

- Even though ZooKeeper does not support linearizable reads, we can be confident that the list

of children

Cobtained above does not miss any clients that came before, since it is preceded by a write operation. If the write operation resolves, the read operation that follows must be as recent as the state right after the write operation.

Leader Election

Leader elections are commonly used to coordinate between multiple processes in distributed systems, where a leader is “elected” to make decisions which “followers” obey. Raft makes use of leader elections for consistent log replication, and ZooKeeper itself follows a leader replication model, as we will see later.

To build such a primitive, we create a regular data node at path l to

hold metadata for the elction. Then, we again create a sequential node

at l, and watch for changes of the preceding data node, and assume the role

of leader if it ever gets deleted. The following pseudocode describes the

idea more concretely.

Election

1 n = create(l + "/n-", EPHEMEREAL|SEQUENTIAL)

2 C = getChildren(l, false)

3 if n is lowest data node in C, assume leader, exit

4 p = data node in C ordered just before n

5 if exists(p, true) wait for event

6 goto 2The underlying idea for implementing leader election is similar to how we implemented the read/write lock above. Can you spot how we avoided the herd effect? Which guarantees of ZooKeeper prevent two clients from thinking they are both the leaders?

ZooKeeper Implementation

Finally, we discuss some of the interesting aspects of the implementation of ZooKeeper itself, namely how it provides its guarantees, and how it is optimized for real-world throughputs.

Replicated Databases

As discussed, a ZooKeeper service is usually composed of multiple servers working as an ensemble. This allows ZooKeeper to provide high availability by replicating the data nodes on each server. In order to maintain consistency between servers, ZooKeeper opts for a common strategy for horizontal scaling, namely leader replication. More specifically, a server is selected as the leader and the other servers are followers. Further, writes are always routed through the reader and commits when there is a quorum. Note that reads on the other hand can be served by a local replica which may be out-of-date and stale (which is why ZooKeeper does not support linearizable reads), but this allows for higher read throughput.

Zab: An Atomic Broadcast Protocol

ZooKeeper makes use of Zab, an atomic broadcast protocol to provide the strong guarantees as described previously. At a high level, Zab makes use of a majority quorum to commit a proposal to a state change, and guarantees that changes are delivered in order that they were sent and are atomic. ZooKeeper also makes use of Zab for fault tolerance, and uses the protocol to deliver “catch-up” messages since the last snapshot in the event of a server failure.

An important point about Zab is that each state change is recorded

in an idempotent transaction. In other words, applying a particular

transaction multiple times will not affect the final state of the system.

Note that this often requires the leader to execute client requests locally

before proposing a change. For instance, an operation to increment the value

of the data node at path has to be converted to setting the value of the

data node to some value to preserve idempotency.

For more details and theoretical proofs of correctness of Zab, check out the paper here.

Fuzzy Snapshots

Since the data nodes are stored in-memory, each replica has to take snapshots periodically as replaying all transactions from the leader would potentially be too time consuming. Recall that ZooKeeper is wait-free, so the snapshots are fuzzy snapshots, since the implementation does not take a lock on the state of a particular replica. Interestingly, a resulting snapshot may not correspond to the state of ZooKeeper at any point in time (can you think of a series of transactions and snapshot procedure that results in this behavior?). But, since transactions are idempotent, a replica can easily apply them as long as the transactions are stored in the correct order.

Summary

ZooKeeper was initially developed at Yahoo! and used for a variety of Yahoo! services such as the search engine crawler and their distributed pub-sub system, but has seen many more use cases ever since. For instance, the Apache Software Foundation has developed Apache ZooKeeper as an open-source version of ZooKeeper and is widely used for many production applications including Apache Hadoop and Kafka as well as companies including Yelp, Reddit, Facebook, Twitter etc. Its simple interface, reasonable consistency guarantees, and flexible abstractions provides the user with the ability to tailor specific primitives that fit the requirements of a particular system.

P.S. Personally, I first heard about ZooKeeper from an interesting Youtube video from one of my favorite programming channels on building an asynchronous ZooKeeper client in Rust, which is in my opinion a great way to get hands-on experience with interacting with ZooKeeper!