Consensus algorithms hold a very important place in distributed systems design, allowing a cluster of machines to work as a coherent group with failure transparency (i.e. the end user does not know when individual machines in the cluster have failed as long as some are alive). The easiest application to visualize is a replicated key-value store, and we’ll use this to make the discussion on RAFT concrete.

RAFT is an algorithm that allows a cluster of machines to act as a replicated state machine which essentially means that each machine has identical state and changes to that state are carried out in the same order on all the machines. The state for a key-value store will be the key-value pairs, and a replicated state machine means that all the writes(creation and deletion) occur in the same order. This is very useful, because if one of the machines goes down, we have a bunch of other machines with identical state. RAFT does this by managing a replicated log of operations. So in the case of the key-value store, it would look something like:

PUT key:ComputerSystems value:Article1

PUT key:ComputerSystems value:Article2

DELETE key:ComputerSystemsIf all machines in the cluster maintain this log, each machine agrees on the order of log operations and applies the operation to its internal state, we will have a replicated state machine! The challenge is maintenance of the log: how do we ensure that all the machines agree on the order of these log operations in the face of network failures, network latencies, machine failures, and other adversarial conditions. This is what RAFT aims to solve.

A Deeper Dive into RAFT

RAFT implements consensus by first electing a distinguished leader that accepts operations from clients. Clients in this case will be users of the key-value store: if I want to store a value, I’ll connect to the leader over the network and send my request. RAFT does this because it simplifies management of the replicated log. Given this model, consensus is broken up into three independent subproblems:

- Leader Election: how do we choose the leader when the system starts, or when we detect that the current leader has failed?

- Log Replication: how does the leader then ensure that the log entries are replicated on all the machines?

- Safety: how can we ensure that all the machines apply the logs in the same order? In other words, if any machine applies a log entry at a particular index, no server should apply a different entry to that same index.

RAFT Basics

RAFT clusters are made up of an odd number of machines, and a cluster with 2n+1 machines can tolerate n failures, because we want a majority of the machines to be alive at any given time. At any given time, a machine is either a leader, a follower or a candidate. During normal operation, there is exactly one leader and all the other servers are followers, just responding to the leader’s requests. The leader is responsible for client requests and also for maintaining the log. The candidate state occurs in leader election, where this state signifies that the server is a possible contender for the next leader.

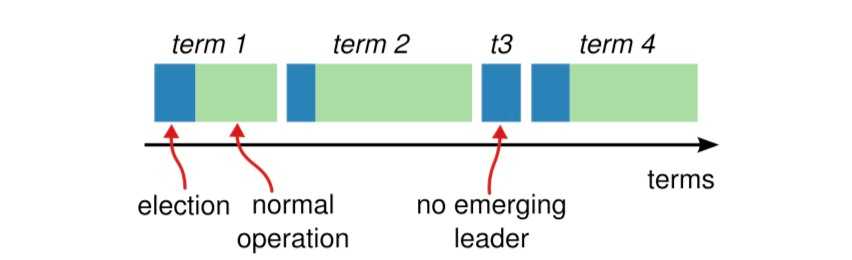

RAFT operation is divided into terms of arbitrary length, numbered with consecutive integers. Each term begins with an election, where the leader for that term is decided. If there is a split vote for leader election, then there will be a randomized backoff, and leader election will take place again. Thus, RAFT ensures that there is only one leader in any given term. The following figure, taken from the paper, illustrates this:

These term numbers are important because they act as a logical clock for the system. Some servers (if in a network partition, or other cases) may miss complete terms. The term numbers helps the machines detect stale leaders and old information.

Communication in this system happens via Remote Procedure Calls (RPCs). This is essentially an abstraction over a traditional TCP connection that allows a server to call a function on another server. One can view it as a simple function call, but where the function executes on another server rather than on the server making the call. The system contains only 2 main RPCs, the AppendEntries RPC and the RequestVotes RPC. We will now look into the first problem of leader election, and how RAFT does this.

Leader Election in RAFT

When servers start up, they are all in the follower state. Leader election happens with heartbeats, which is an important concept in distributed systems. Heartbeats are when servers send out periodic messages to simply indicate that they are alive. If a server sees a certain period of time without a heartbeat, it will assume that the leader has died, and then will transition to the candidate state. The threshold of time before the follower concludes that the leader is dead is called an election timeout. Note that these election timeouts are randomized per server, and so they won’t all transition into candidacy at the same time.

When a follower becomes a candidate, it votes for itself and then issues RequestVote RPCs to all the other servers in the cluster. A candidate will become a leader if it receives votes from a majority of the servers in the cluster. It also may be the case where there is a race: two servers transition into candidacy at about the same time. Since we are using a majority vote and each server can only vote for one server, only one can win the race. Thus, if a server is in the candidate stage and it recieves an AppendEntries RPC from another server with a term number that is atleast as large as its own term number, it will recognize that another server has won the race and will transition back to the follower state.

It may also be the case that there is a split vote, if many followers become candidates at the same time. IN this case, the candidate will time-out and then start a new election by incrementing its term and starting a new round of RequestVote RPCs. To prevent a livelock (where the split votes occur indefinitely), RAFT adds randomization to the election timeouts, and they are randomly chose from a fixed interval (150ms-300ms). This randomization also means that on failure of the leader, only one of the server’s will time-out, and so there will be only one server requesting votes reducing the chance of a split vote. Note that the 150ms-300ms range comes from experimentation, and ensures that network delays in the leader’s heartbeats do not frequently trigger new leader elections while the current leader is alive.

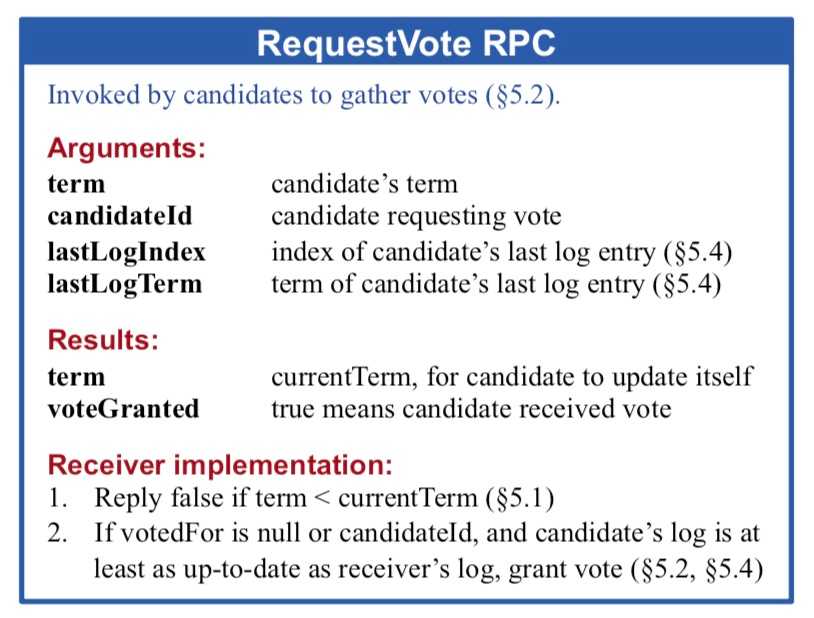

See the figure (taken from the paper) below for an explanation of the mechanism of the RequestVote RPC.

Log Replication in RAFT

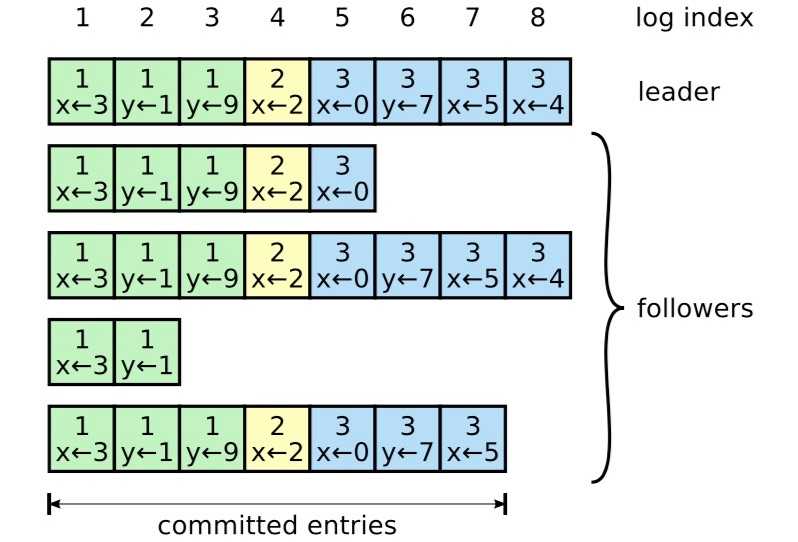

Once a leader has been elected, it begins servicing client requests. Each request contains a command to be executed by the replicated state machines. The leader appends this command to its own log, and then issues AppendEntries RPCs in parallel to all the servers in the cluster (spins up a thread to send AppendEntries RPCs). If the follower doesn’t respond due to a crash or loss of network packets, the AppendEntries RPC will be retried indefinitely, even after responding to the client. Logs are organized as follows, with each entry storing a state machine command, along with the term number. In the figure below (taken from the paper), the state consists of two variables x and y, whose values are updated.

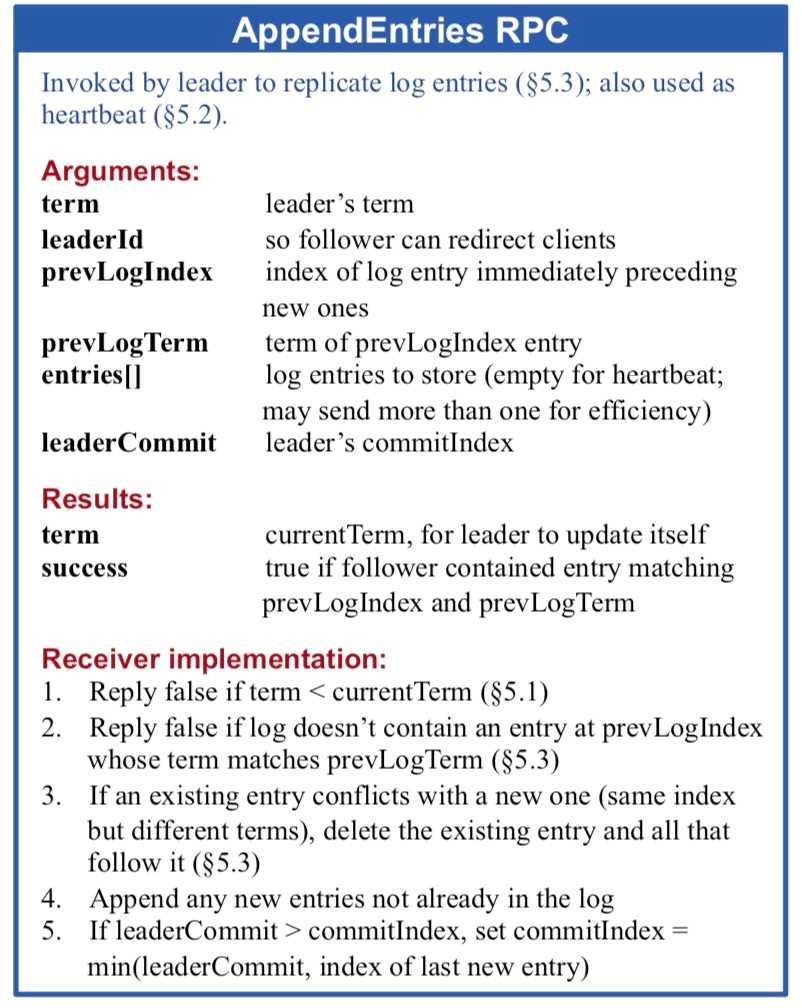

Entries need to be committed to the log, they cannot executed as soon as they’re received, because RAFT has to guarantee that this entry will be durable. In other words, if this log entry does not find its way onto a majority of the servers, no one should apply it to the state, as this risks divergence. The leader commits an entry, i.e. allows it to be applied to the state machine when a majority of servers have appended it to their local logs. A committing of a particular log index, also commits all previous entries not yet committed. The leader keeps track of the highest entry it has committed, and then sends that in the AppendEntries RPCs for the other servers to eventually find out. The AppendEntries RPC works as shown in the figure (taken from the paper) below.

This RPC was designed to maintain a high degree of coherence between logs on different servers. In particular, RAFT maintains the Log Matching Property, which states that:

- If two entries in different logs have the same index and term, then they store the same command.

- If two entries in different logs have the same index and term, then the logs are identical in all preceding entries.

The first property follows from the fact that a leader creates at most one entry with a given log index in a given term, and log entries never change position. We will dive into this deeper while looking at some failure scenarios. The second property follows from the simple consistency check performed by the AppendEntries RPC. As shown above, arguments to the AppendEntries RPC include prevLogIndex and prevLogTerm which are the log index and term of the entry immediately preceding the entries sent. If the follower’s log does not match this, it refuses the new entries. This acts as an induction step, always ensuring that the logs agree.

In the absence of any failures, there will be no case where the logs disagree. However, crashes can leave logs inconsistent. A follower might crash and come back up after some log entries have already been committed (remember, the system will continue to function if a majority of the servers are up), and thus might be missing some entries. The follower might also have extra entries not present on the current leader. To test your understanding, try to think of a scenario where a follower in a given term can have extra entries that are not present in the leader’s log (hint : what happens if the leader in the preceding term receives entries by crashes before it can replicate them). RAFT handles the divergence in logs in a given term by forcing the follower’s logs to agree with the leader’s log. This means that any entries not on the leader’s log will be overwritten or deleted. This occurs through the AppendEntries RPC. Notice that if the follower’s log does not agree with the leader’s log, the AppendEntries consistency check will fail, and the new entries will get rejected. Once this happens, the leader will decrement the prevLogIndex and send the entry at the new prevLogIndex. This will continue until either there is a match, or the follower is forced to overwrite its log completely with the entire log of the leader. This is a clever method because the leader does not have to take any additional or special measures to ensure log consistency - the AppendEntries RPC will take care of that.

Safety in RAFT

The rewriting of logs seems potentially dangerous. How can we be sure that we do not rewrite an entry that has already been applied to the state machine? If someone sends a PUT request and that is overwritten, the client will suddenly and inexplicably find his key absent from the database, which is unacceptable behavior. We need to add one more feature to RAFT leader election to ensure that safety is maintained.

Essentially, what we want is that every leader who gets elected should have a log that contains all the committed entries. Recall that committed entries are those that have already been applied to the state machine. The need for this is evident, if the newly elected leader did not contain all the committed entries, then it would overwrite logs such that some committed entries would be deleted. RAFT uses the voting process to prevent a candidate from winning an election unless its log contains all the committed entries. A candidate must contact a majority of the servers to get elected, and it will only recieve a vote if its log is atlease as up-to-date as the server it is requesting a vote from. This is where the importance of the majority comes in. We know that in order for an entry to be committed, it has to be replicated on a majority of the servers. Therefore, the candidate will need to receive at least one vote from a server that has a log that contains all the committed entries, implying that the candidate will have a log at least as up-to-date as the server in question. This means that all elected leaders will contain all committed entries, and we will never find an unsafe scenario.

For a more formal proof of the Safety property, see the RAFT paper.

Zooming Out and Applications

We will zoom out and now look at how clients interact with a RAFT cluster. Clients of RAFT are supposed to send all their requests to the leader. On start-up, it connects to a randomly chosen server in the cluster. If this is not the leader, the client’s request will be rejected and the server will send it information about the most recent leader it has heard from. The client will then retry with the leader. If the leader crashes before returning a response, or before accepting the request, the client request times out, and it will then try again with randomly chosen servers.

Once a client has found the leader, it will send it a request for some operation. The leader will append this request to the log, and then attempt to replicate it on a majority of the servers. If it’s successful in doing so, i.e. more than half of the AppendEntries RPCs are successful (return true), it will apply the command to its own state and reply to the client. If the leader fails during this process, as mentioned above, the client will time-out and retry. If the leader is unable to replicate this on a majority of servers, the request will not get completed. The client will similarly time-out and retry.

RAFT’s clean and understandable design, consisting of only two main RPCs, makes it an attractive choice for any company looking for a way to maintain a replicated state machine. This is especially true for database and data storage companies, like CockroachDB and MongoDB. RAFT is used to manage their replication layers, which is a layer of abstraction that handles storing multiple copies of the data to provide redundancy. Hashicorp’s Consul also uses RAFT to maintain system reliability. Messaging solutions such as RabbitMQ use it as well.

Conclusion

We thus saw how RAFT maintains a distributed log amongst multiple machines. RAFT is similar to Paxos (a very widely used consensus algorithm) in terms of performance and guarantees, but is a lot more understandable and implementable (try implementing a distributed version of RAFT if you want, message the distributed-systems channel on Slack for tips on how to get started). It also touches on a lot of topics that are core to distributed systems such as fault tolerance, a leader-follower model, RPCs for communication, heartbeats and consensus.

Useful References

If you want to dive deeper into RAFT, read the original RAFT paper. There is also this talk by Professor John Ousterhout, one of the authors of the original paper. This website also contains more talks and visualizations about RAFT. Of course, if you have any specific questions, feel free to post in the distributed-channels Slack.